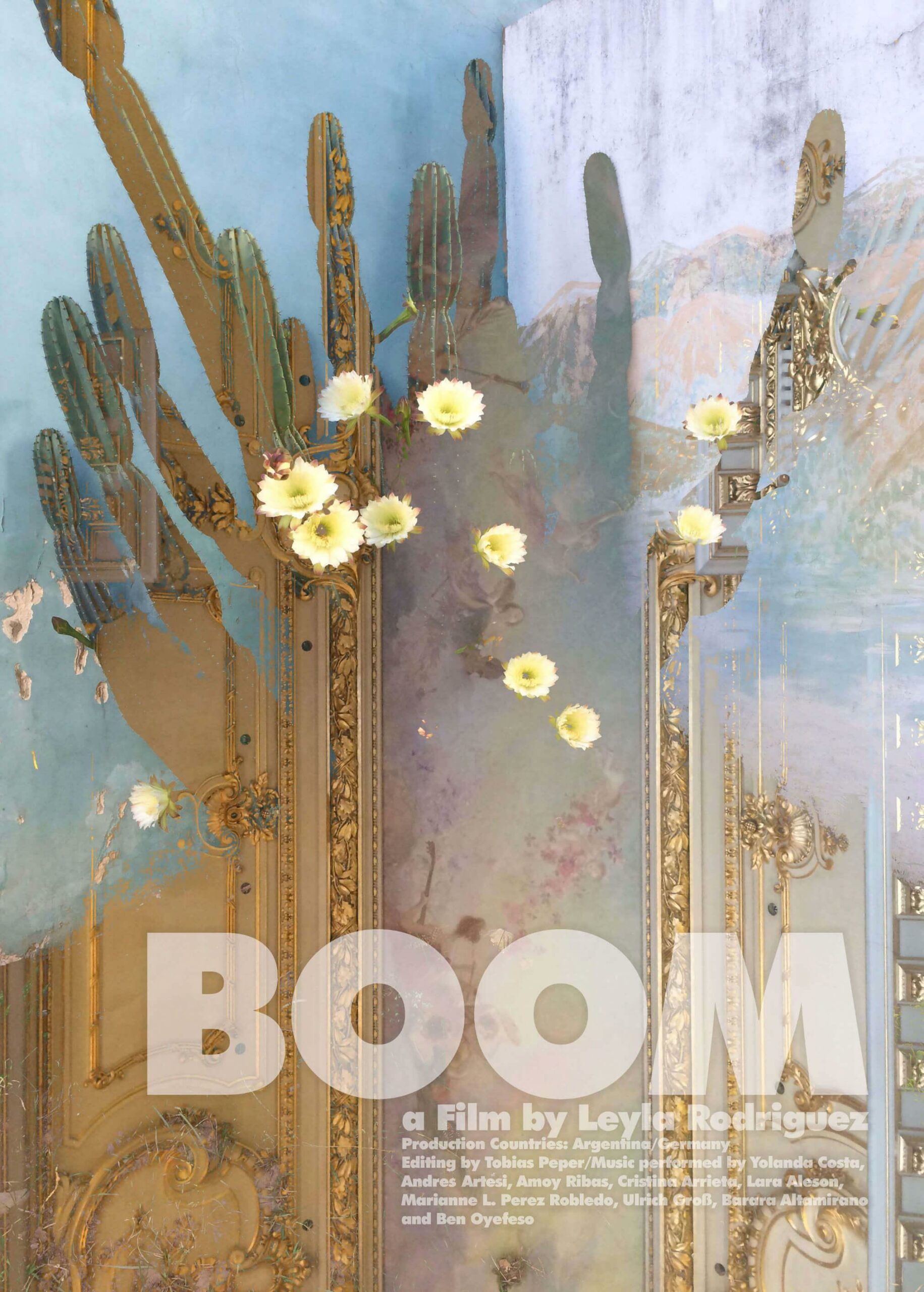

BOOM

HD | 06:34 Min. | Color | Sound | 2018

Argentina and Germany

BOOM begins with the at times somewhat laborious but nevertheless decisive path of a tortoise along an exotic forest floor. The impression of a journey with a specific destination at its end is enhanced by briefly inserted sequences of a nighttime view out of a moving train. The animal finally reaches its destination within the story: a tall, lavishly flowering cactus growing in a corner between two multifaceted walls. The plant nestles into its backdrop in a picturesque manner, just as the background appears to reference the plant. In this regard BOOM feels like a kind of epilogue to Rodriguez’s earlier films (Optimistic Cover, 2015, Supreme Presence, 2016, Interior Season, 2017, Homeless, 2017) in which a collaboration of nature, culture and identity is negotiated as an overriding question. In this context nature could be a romantic, misty-eyed place of longing or a placeholder for culture and identity – just as architecture, technology and urban landscapes are depicted as something organic, something that changes and is animated. By using an academic classification of the current relation between humans and nature in the age of the Anthropocene, theoreticians such as Bruno Latour endeavour – in a comparable manner – to abolish the binary approach to nature and culture at the theoretical level and to make space for fluctuations in the two poles. In this sense nature is no longer seen as a divinely omnipotent entity that humans must submit to or whose destruction they penitently observe; rather, parameters supposedly set by nature, such as gender and role images, are deconstructed.

In BOOM the cactus takes on a transcending role as nature personified, illustrating its relationship to the culture surrounding it: it grows between two high walls that maybe left a little room because of it or in whose protection from the elements it was able to flourish particularly well. It loses it magnificent flowers or is robbed of them. And finally a masked figure resolutely severs one of its many arms and holds it, wrapped in a gold band – up high like a trophy. Robbed in this fashion the cactus loses some of its grandeur and appears lost and broken despite its size and its spines. While images of nature, culture and personal photographs enter associative analogies as they are presented in a rapid sequence in the middle section of the film, the final shot takes us back to the scene around the cactus. Instead of being adorned by flowers it is now decorated in gold strips of adhesive tape that are being touched in a conciliatory manner by the masked figure. The tortoise too bears two gold strips of adhesive tape on its shell for some time, appearing to leave the events towards the underbrush. The film ends with a photograph of a young girl in front of a wall with two tall cactuses next to her. BOOM addresses the synthesis of nature and culture and their reciprocal potential and rivalry in a playful manner and it emphasizes a continued existence for both sides as a carrier of memories and identity.

BOOM beginnt mit einem teils etwas beschwerlichen aber dennoch entschlossenen Weg einer Schildkröte über einen exotischen Waldboden. Der Charakter einer Reise, an dessen Ende ein spezifisches Ziel steht, wird dabei verstärkt durch kurze eingeschobene Sequenzen eines nächtlichen Blicks aus einem fahrenden Zug. Innerhalb der Narration erreicht das Tier schließlich sein Ziel: Einen übermannshohen üppig blühenden Kaktus, der in einer Ecke zwischen zwei facettenreich gestalteten Mauern wächst. Auf malerische Weise fügt sich die Pflanze in ihren Hintergrund, ebenso wie sich auch der Hintergrund auf die Pflanze zu beziehen scheint. BOOM wirkt in dieser Hinsicht als eine Art Epilog Rodriguez vorhergegangener Filme (Optimistic Cover, 2015, Supreme Presence, 2016, Interior Season 2017, Homeless, 2017) innerhalb derer als übergeordnete Frage ein Zusammenwirken von Natur, Kultur und Identität verhandelt wird. Natur kann dabei zu einem romantisch verklärten Sehnsuchtsort oder Platzhalter für Kultur und Identität werden ebenso wie Architektur, Technik und Stadtlandschaften als etwas Organisches, sich Wandelndes und Belebtes gezeigt werden. Mit einer wissenschaftlichen Einordnung der gegenwärtigen Mensch-Natur-Relation im Zeitalter des Anthropozän unternehmen Theoretiker wie Bruno Latour – in vergleichbarer Weise – den Versuch eine Binarität von Natur und Kultur auf theoretischer Ebene aufzuheben und ein Changieren der beiden Pole einzuräumen. Die Natur gilt demnach nicht mehr als göttlich übermächtige Einheit, der sich der Mensch zu unterwerfen hat, oder dessen Zerstörung er reumütig betrachtet, vielmehr werden vermeintlich naturgegebene Parameter wie Geschlecht und Rollenbilder dekonstruiert.

In BOOM übernimmt der Kaktus eine transzendierende Rolle als personifizierte Natur und illustriert sein Verhältnis zu der ihn umgebenden Kultur: Er wächst zwischen zwei hohen Mauern, die vielleicht seinetwegen etwas Raum gelassen haben oder in dessen Schutz vor Witterung er besonders ausladend gedeihen konnte. Er verliert seine prächtigen Blüten oder wird dieser beraubt. Und schließlich kappt – mit Bestimmtheit – eine maskierte Gestalt einen seiner vielen Arme und hält ihn, umwunden von einem goldenen Band, wie eine Trophäe in die Höhe. Derartig beraubt büßt der Kaktus an Erhabenheit ein und erscheint trotz seiner Größe und Stacheln verloren und gebrochen. Während im Mittelteil des Filmes in einer schnellen Abfolge Bilder von Natur, Kultur sowie persönliche Fotografien assoziative Analogien eingehen, führt die letzte Einstellung zurück zu der Szenerie um den Kaktus. Anstelle von Blüten zieren ihn nun goldene Klebebandstreifen, die von der maskierten Gestalt versöhnlich berührt werden. Auch die Schildkröte, trägt für einige Zeit zwei goldene Streifen Klebeband auf ihrem Panzer und scheint das Geschehen in Richtung Unterholz zu verlassen. Der Film endet mit einer Fotografie von einem kleinen Mädchen vor einer Mauer, neben ihr zwei hohe Kakteen. Auf spielerische Weise erzählt BOOM von einer Synthese von Natur und Kultur, von deren gegenseitigem Potenzial und Rivalität, und betont dabei für beide Seiten ein Fortbestehen als Träger von Erinnerungen und Identität.

Rosa Windt

BOOM s’ouvre sur le chemin laborieux bien que décisif parcouru par une tortue sur le sol d’une forêt exotique. L’impression d’un voyage à la destination précise est soulignée par l’insertion de brèves séquences d’un paysage nocturne filmé d’un train en mouvement. L’animal atteint finalement sa destination au sein de l’histoire : un grand cactus somptueusement fleuri planté dans un coin, à l’intersection de deux murs. La plante est nichée dans son décor d’une manière pittoresque, alors que l’arrière-plan semble lui faire référence. En ce sens, BOOM se présente comme une sorte d’épilogue aux précédents films de Rodriguez (Optimistic Cover, 2015, Supreme Presence, 2016, Interior Season, 2017, Homeless, 2017) dans lesquels une collaboration entre nature, culture et identité est négociée comme une question majeure. Dans ce contexte, la nature serait un endroit de désir romantique et tire-larmes ou un substitut à la culture et à l’identité – tout comme l’architecture, la technologie et les paysages urbains sont décrits comme quelque-chose d’organique, mouvant et animé. L’utilisation de la classification académique des relations actuelles entre les humains et la nature à l’ère de l’Anthropocène, des théoriciens comme Bruno Latour s’efforce – d’une façon comparable – d’abolir l’approche théorique binaire de la nature et de la culture pour créer un espace de fluctuation entre les deux pôles. Alors, la nature n’est plus vue comme une entité divine et omnipotente à laquelle les humains doivent se soumettre ou dont ils observent, pénitents, la destruction. Les paramètres supposément fixés par la nature, tels la notion de genre et les modèles, sont plutôt déconstruits.

Dans BOOM, le cactus joue un rôle transcendant, celui de la nature personnifiée, illustrant sa relation à la culture qui l’entoure : il grandit entre deux hauts murs qui lui ont peut-être laissé un peu de place ou dont la protection lui a permis de produire de si belles fleurs. Il perd ses magnifiques fleurs ou elles lui sont volées. Finalement, une figure masquée tranche résolument un de ses nombreux bras et le porte fièrement, enroulé dans une bande dorée, tel un trophée. Volé de cette manière, le cactus perd de sa grandeur et apparaît perdu et cassé malgré sa taille et ses épines. Alors que des images de nature, de culture et des photographies personnelles intègrent des analogies par association, comme lors de la rapide séquence qui survient au milieu du film, le plan final nous ramène à une scène autour du cactus. Mais cette fois, au lieu d’être paré de ses fleurs, il est décoré de bandes adhésives dorées, touchées dans un esprit de conciliation par la figure masquée. La tortue aussi porte deux bandes adhésives dorées sur sa carapace pendant quelques temps, elle semble quitter le lieu des évènements en passant par les taillis. Le film se clôt sur la photographie d’une jeune fille devant un mur, près de deux grands cactus. BOOM aborde de manière ludique la synthèse de la nature et de la culture ainsi que leur potentiel et leur rivalité réciproques. Il met ainsi l’accent sur l’existence continue des deux parties en tant que porteuses de souvenirs et d’identité.

With a series of seven short films in all, Leyla Rodriguez composes sequences of family and identity. In many cases, penetrating autobiographical and intimate shots are assembled, developing the character of moving collages. Ahistorical, multiply ambiguous, symbolically charged images suggest narratives that are ultimately left open. In this way, the films do not generate a stringent view of time or narrative, but in a kind of endless loop form variable interpretations and possibilities of entry. The relationship between nature, culture, ‘Heimat’ and ‘dépaysement’, comes across as a superordinate and recurring principle, generating the melancholy and yearning that overlie the films.

Leyla Rodriguez comes from a musical family. She grew up under the military dictatorship in Argentina that lasted from 1976 to 1983, and in 1984 she finally moved to Germany. Many of her relatives remain in Argentina, while others emigrated to the United States, Brazil and Australia, so that the once close-knit family has become dispersed. What remained was a feeling of lack of identity and a home for ever lost.

Various members of the family are musically integrated film by film, forming a focal point of the narrative without themselves appearing. In their place various shots of landscape, wild and domestic animals and Rodriguez herself – disguised as a hooded figure, as a hybrid between animal, human and textile – take on the role of abstract personifications. Old melodies, some composed by family members, are supplemented by new ones and back up the pictorial narratives. Sound sequences dominate the different scenes, linking them and becoming lead actors in their own right.

Much of the film material shows excerpts from the everyday life of the artist and creates a random, casual structure. In the expansion of often strange-looking images, aesthetic affinities arise between the images, creating a parallel world between order and disorder. The film medium alternates between photographic, pictorial and performative episodes and no clear categorization is possible.

The film series starts with The Separation Loop, dating from 2015, followed by Optimistic Cover, 2015, Supreme Presence, 2016, Interior Season 2017, Homeless, 2017, Hermetica, 2018 and the final film, completed 2018, Boom.

Mit einer Reihe von insgesamt sieben Kurz-Filmen entwirft Leyla Rodriguez Sequenzen von Familie und Identität. Vielfach werden dabei eindringliche autobiografische und intime Aufnahmen assembliert und entwickeln den Charakter bewegter Collagen. Ahistorische, mehrdeutige, skurrile Bilder, Musik und Charaktere suggerieren Narrative, die nicht eingelöst werden. Die Filme generieren so keine stringente Zeitauffassung oder Erzählung, sondern bilden in einer Art Endlosschleife variable Einstiegsmöglichkeiten und Lesarten. Als ein übergeordnetes und wiederkehrendes Prinzip erscheint dabei das Verhältnis von Natur, Kultur, Heimat und Heimatlosigkeit und erzeugt eine die Filme überlagernde Melancholie und Sehnsucht.

Leyla Rodriguez stammt aus einer Musikerfamilie. Sie wuchs während der von 1976 bis 1983 andauernden Militärdiktatur in Argentinien auf und immigrierte 1984 schließlich nach Deutschland. Während Teile der Familie in Argentinien verblieben, wanderten andere nach Amerika, Brasilien und Australien aus, und der ehemals enge Verbund verlor sich in kleinen Gruppen. Ein Gefühl der Identitätslosigkeit und einer für immer verlorenen Heimat blieb.

Verschiedene Mitglieder der Familie werden Film um Film musikalisch integriert und bilden einen Schwerpunkt der Erzählung, ohne dabei selbst in Erscheinung zu treten. An ihrer Stelle übernehmen verschiedene Aufnahmen von Landschaft, Wild- und Hausieren sowie Rodriguez selbst — verkleidet als vermummte Gestalt, als Hybrid zwischen Tier, Mensch und Textil — abstrakte Personifikationen. Alte Melodien, teils von Familienangehörigen komponiert, werden durch neue ergänzt und tragen die bildnerischen Erzählungen. Klangfolgen dominieren die verschiedenen Szenen, verknüpfen diese und werden zu Hauptakteuren.

Ein Großteil des filmischen Materials zeigt Ausschnitte aus dem Alltag der Künstlerin und entwirft eine vom Zufall geleitete, beiläufige Struktur. In der Erweiterung oft seltsam anmutender Aufnahmen, ergeben sich zwischen den Bildern ästhetische Verwandtschaften und erzeugen eine Parallelwelt zwischen Ordnung und Unordnung. Das Medium Film changiert dabei zwischen fotografischen, malerischen und performativen Episoden und verhindert eindeutige Kategorien.

Rosa Windt